image by Marieke VaNoon

At first sight, international non-profit professionals live extraordinary, purpose-driven lives. The “development set” travel the world doing worthy work, saving strangers in intriguing places. Their tales of disaster, poverty, and war are often jaw-dropping, action-packed adventures – the stuff of movies.

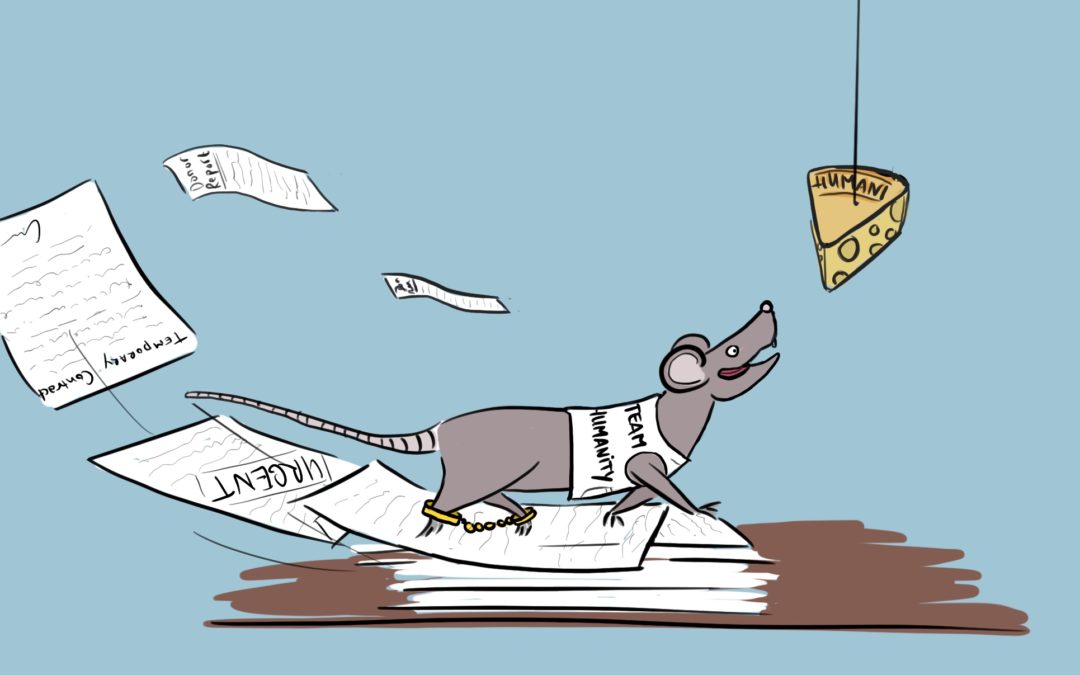

So how could this life be anything like the drudgery of the rat race? Well, here’s five potential traps in the international non-profit rat race:

1. The Precarity Trap

Job security, benefits, labour rights, material and psychological stability are rare in the humanitarian sector. Just to enter this race you’ll need to survive a precarious period of unpaid labour as an intern or volunteer. Eventually, when you do land a paid job, it’s likely to be temporary. You’ll spend your life pinging around the planet, trapped in an endless, competitive race for the next – and then the next – unstable gig. The susceptibility of the international non-profit precariat to exploitation has hit the headlines – #aidtoo. Far from meritocracy, it’s a structurally biased race. Getting ahead is often more about where you come from, your gender, class and your race. Should you fall victim to discrimination, harassment, or bullying, you may be left unprotected by unions or laws. It’s an exhausting, competitive, structurally unequal global scramble for cheese.

2. The Paper Emergency Trap

From my first deployment during the war in Bosnia in 1994 to the present day, I’ve witnessed just how powerful and important humanitarian action can be. Yet, today, many tell me that they feel their work is a pointless bureaucratic paper chase. Far from responding to real crises, they say they spend their days dealing with paper emergencies, created by large organisational beasts that feed themselves: HQ and funders “urgently” need that report, or a rehash of the same old proposal which primarily meets donors’, rather than real people’s needs. Are we, as someone has suggested, seeing a rise in humanitarian “bulls**t jobs?” I’m not sure I’d go that far. But many tell me it’s repetitive work with questionable impact. It’s sold as so important that they’re left guilt-stricken at the mere thought of taking time off.

3. The Golden Handcuff Trap

When deployed, the travel, exotic pad, domestic staff and driver are very nice. It’s a gilded life that’s a stark contrast to that of national colleagues. But there’s a hefty price to pay when the handcuffs are taken off: Any material accumulation quickly dissipates during unemployment or unpaid leave in-between gigs. Unemployment is often lengthy and indefinite, especially if burnout kicks in. At that point, the idea of going “home” might well appeal. But by now the perpetual humanitarian expat may be so disconnected and globally feral that they’ve lost all sense of where home actually is. Removing the golden handcuffs necessitates a downgrade in lifestyle and painful cognitive dissonance – both unavoidable features of re-entry into “normal” life. Ironically, most end up staying in some acutely uncomfortable comfort zones because it’s far less challenging to keep pinging from disaster to war zone than it is to go home.

4. The Burnout Trap

I’ve spoken extensively about the occupational hazards of chronic stress and trauma. Research, including my own, shows that ingrained cultures of martyrdom and unwellness, coupled with mismanagement, are a potent recipe for burnout. This adrenaline-fuelled life may be addictive, but in a sector where staff wellbeing and care are an afterthought, professional longevity is rare. When one’s expiry date comes up, the exit often kicks off with a lengthy period of sick or unpaid leave. It’s an emotional and existential rollercoaster. Yet, it is possible to minimise the negative side effects of the international non-profit life. In my work, every day, I help committed people formulate creative and impactful individual and organisational strategies that go a long way to prevent and mitigate burnout.

5. The Ego Trap

The longer you stay in the race, the more your personal and professional identity merges with your non-prifit life. You might start thinking that you’ll never be able to do anything as worthy or important as this work and that if you step aside you’ll leave a gap that no one else could ever fill. If you do leave, you’ll be stripped of your identity, and endure the guilt of letting Team Humanity down. The ego trap is the most hazardous part of this race because it tricks you into forgetting the harsh realities of the precarity, paper emergency, golden handcuff, and burnout traps. But if you do choose to stay, you risk waking up one morning as you slide towards old age realising that you’ve got no security, stability or a place you can call home.

It’s tough stuff. There’s no easy answers. But, in my coaching practice I’ve seen that it is possible to find creative and inspiring solutions both within, and beyond, international non-profit work. I’d love to hear about your experiences and what made things better for you.

Liz Griffin stepped away from the international non-profit rat race after 20 years of service with the UN, NGOs and as a full time Professor of Human Rights Law.

Liz is Fellow, Centre for Armed Conflict and Crisis, University of Essex and Extraordinary Lecturer, Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria). She is a full time Professional Certified Coach, Solution Focused Practitioner, Mentor and Senior Yoga Alliance Professional. Find out more about Liz here.

The same could be said about working by the Council of Europe. That’s a pity.

Quo Vadis is our Humanitarian Leader like Ghandi and MLK and Carter and Obama? Can the Moral Imperative ever disappear? Tears never lie, they just help us recover.

Succinct, Liz! Thanks. On something related, I confess that I find the ‘poor me’ discourse (‘we suffer from vicarious trauma and stress’, etc.) now so common in the field a little wearisome, That combined with the gap between the values espoused in abstract by so many humanitarian ‘professionals’ and their actions in reality, as well as the sheer mediocrity of many in the field with the implications that has for actual rights holders facing actual challenges. I have long since come to the conclusion that the field’s high salaries – rather than attracting the best – actually retain the most mediocre or incompetent, who then dedicate their energy to maintaining their privilege, undermining the aims of the work and stultifying the institutions. These reflections do not reflect the many excellent professionals working in this area of course, bUt my impression is that they are a relative minority. The mediocre – or worse – quotient reflect a much larger part of the sector than I would have expected or hoped years ago, sadly.

And in some cases we have organizations that are humanitarian but give inhuman contacts to their staff. An example is the WFP consultancy contract which is totally inhuman and the fixed term contracts are given to a few who have connections with the seniors at higher level. The audit deport which was released some time in previous years noted some of these loopholes. They cannot learn from other agencies that have same short term contracts with better benefits including basics like leave days. What a shame- time for humanitarian organizations to change.